If you’re like many product people you’ve wondered why some things aren’t getting done, worried that you’re overstepping your bounds, or got irked that someone else is overstepping their bounds.

A lot of this confusion comes from the complicated nature of product people roles and titles. It doesn’t help matters that different organizations interpret those roles and titles differently.

In the hope of providing a bit of clarity, this post explores product roles and titles. We’ll start out by defining roles and titles, then we’ll explore roles and titles in an external product setting and roles and titles in an internal product setting.

Definitions

A role is a function that you play in an organization or with respect to a product or project. Roles describe what you do and is often used as shorthand for a set of responsibilities you fulfill.

A title is how you present yourself outside the organization. It is, ironically, what you reply when someone asks you what you do for a living (ie “I’m a product manager”). The title can often be used as shorthand for the set of skills you have and it is likely to be what gets listed on a job description. You will also see variations of job titles as a way to denote seniority and hierarchy, such as this common hierarchy for product managers.

Roles and titles are confusing because they are often referred to using the same terms.

To avoid confusion in this post I’ll refer to the roles in terms of the function they perform (product management, product ownership, or business analysis) and titles using the terms that you’ll most likely see on a job ad or business card (product manager, product owner, or business analyst)

Typical product people roles

The product management role focuses on understanding an organization’s customers, understanding their needs, and determining whether it’s worth it for their organization to satisfy those needs. This function primarily deals with an organization’s customers and users.

The product ownership role focuses on supporting the team delivering the solution and making sure that team has the information necessary to deliver the right solution effectively. This function primarily deals with the delivery team.

The business analysis role focuses on understanding the business processes and business rules necessary to satisfy your customers’ needs. This role primarily deals with subject matter experts—and to some extent users.

Typical product people titles

The product manager title is typically applied to product people who are responsible for a product and its outcome on the customer and the business. You’ll typically see product manager titles in the product development part of an organization. I say typically because some organizations have titled product managers working in internal product situations (more on that in a bit). Sometimes it’s due to the organization moving toward a product way of working. Sometimes it’s because of SAFe.

The product owner title started out as one of the roles from the Scrum framework. It became a title when organizations started looking to hire product people explicitly to fill the product ownership role. Although the name implies that a product owner “owns” responsibility for a product, in practice most people with this title end up owning the product backlog and interaction with the product team. Relative to product managers and business analysts, there aren’t a lot of people with the explicit product owner title, but there are a lot of people playing the product ownership role.

The business analyst title (when applied to IT and software development) has been around for a while. Back in the day, business analysts were the people who tried to help business people and technology people understand each other. To put it a little more formally, business analysts elicit, analyze, and document requirements to find answers to known problems and deal with complicated systems. Business analysts are usually found in IT organizations, process improvement organizations, or organizations that develop products for internal use.

The roles explored

You can’t assume that if your title is product manager that all you’ll do is product management as described above.

It’s not unusual to see:

- a product manager doing product management and product ownership

- a business analyst doing product ownership and business analysis

- someone who does not have a product manager, product owner, or business analyst title asked to fill a product ownership role.

In addition, different organizations use titles in a variety of ways. So in an attempt to bring some clarity to the exploration, the rest of this post focuses on roles.

Product management

Melissa Perri, in her Product Management Foundations online course, describes product management as effectively solving problems for customers while achieving business goals. It’s about becoming an expert in the needs of your organization’s customers and identifying ways to satisfy those needs that are beneficial to your organization.

As a result, product management requires a balance between the needs of your customers and the needs of your organization.

Some product management techniques help you build and maintain a direct, meaningful connection with your organization’s customers. Other product management techniques help you to assess those needs against your organization’s strategy and business plan. Still other techniques help you make decisions about what problems to solve and what products to build and update.

Product management also deals with the business aspects of selling the product and making it available to your organization’s customers.

In an external product context, product management is often the function that incorporates everything product people do. Product ownership, then, is a subset of product management and business analysis doesn’t necessarily exist as a separate function.

Product Ownership

The product ownership function was originally created to describe the activities that the product owner role does in the Scrum framework. Because Scrum was created to guide the work of a software development team, the product ownership role tends to focus on what a software development team expects their product person to do. You can see this focus in the definition of product owner in the Scrum Guide.

As a result, product ownership focuses almost entirely on the relationship with the team developing a solution. The related techniques provide clear direction regarding the right things to build and include things such as creating backlog items, refining the backlog, and providing information about backlog items. What often gets left unsaid is how product owners go about making those decisions, or how much they should look externally to understand the market.

The creation of the product ownership role has caused some angst and confusion in product circles. Should there be a product manager and product owner? Should there be only one? If both, who leads whom?

Your answer to those questions will vary based on the size of your organization and whether you associate more with the product management community (product ownership is one of the many things that product managers do) or the Scrum community (sure, product owners do product management stuff too, but what really matters is that every team has a product owner).

Business Analysis

The International Institute of Business Analysis (IIBA) describes business analysis as “the practice of enabling change in the context of an enterprise by defining needs and recommending solutions that deliver value to stakeholders.” In some respects, you could interpret that as product management applied to internal products.

In practice, however, there are some key differences. Most business analysis functions are in a position to support decision making but not necessarily make the decisions. One advantage of moving to a product perspective is changing this such that business analysis functions are better positioned to influence and even make key decisions.

The main activity that differentiates business analysis from product management and product ownership is the focus on understanding business processes, data, and business rules.

Business analysts tend to focus on the needs of businesses and stakeholders.

Titles and roles in an external product setting

Understanding the difference between roles and titles is informative. In order for that knowledge to be truly useful, you need to understand how roles and titles relate in specific contexts.

A good way to focus on contexts is to split them between an external product setting and internal product setting. In an external product setting you work directly on a product for sale to customers. In an internal product setting you work on a product that enables your organization to provide products and services to customers.

I’d like to explore an external product setting in order to better understand the relationship between product managers and product owners. Next, we’ll look at internal product settings where business analysts play a much bigger role.

External Product Roles

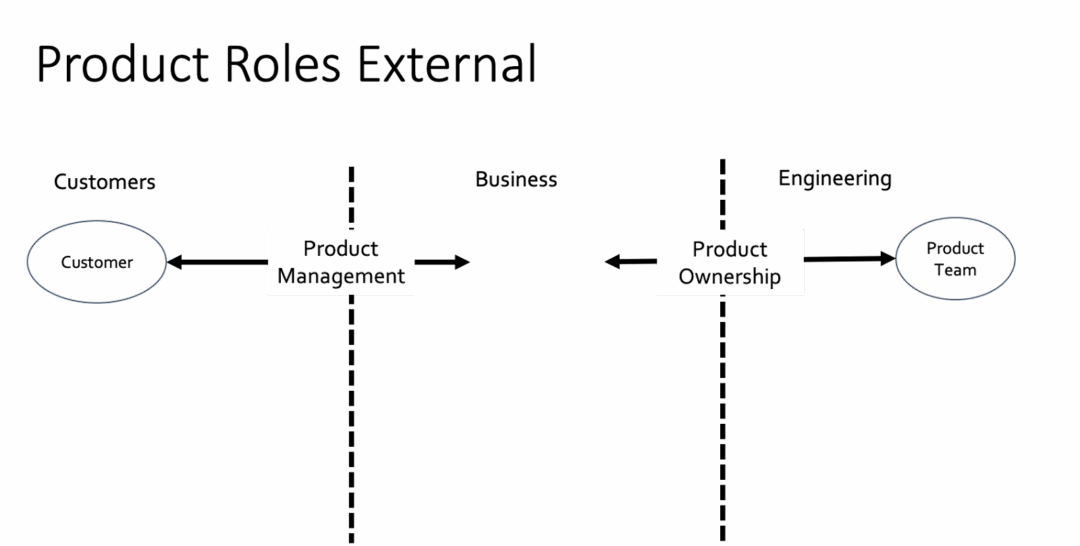

When you look at the roles involved in external product settings there are two roles that you are most likely going to fill.

You fill the product management role when you work to understand customers and are outward focused.

You fill the product ownership role when you build shared understanding with your product team and are inward focused.

Business analysis is rarely a separate role in external product setting and is absorbed into the other two. I find that business analysis is much more prevalent in internal product settings so I’ll explore how that role gets involved in the whole role/title scheme in the next section.

Models for organizing product people for external products

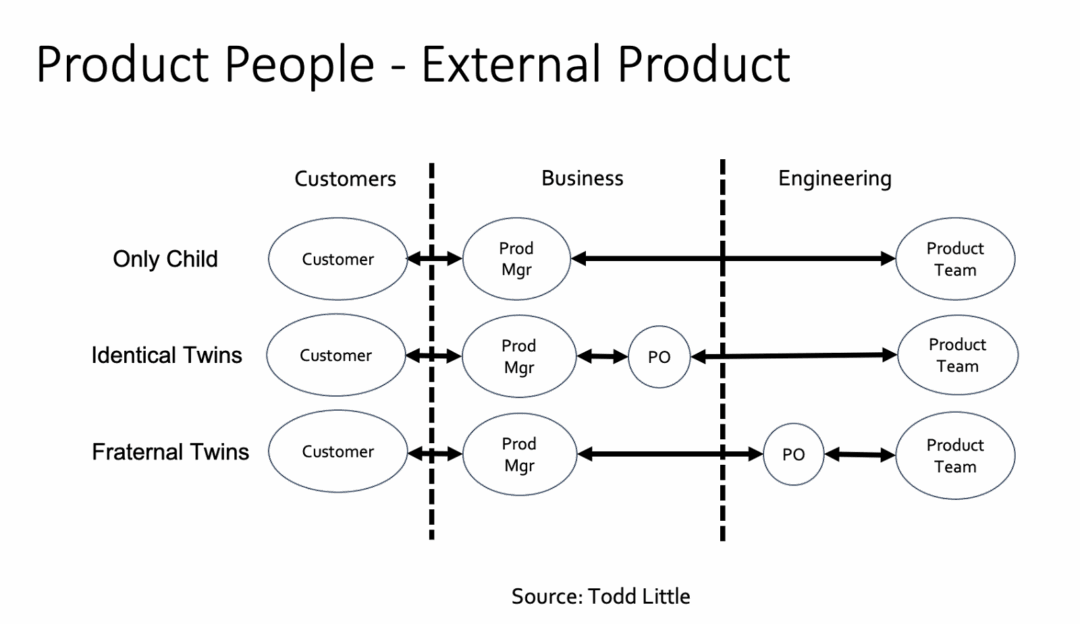

Now that you have two primary product people roles, the question becomes how do you organize the people that fill those roles. This is where the diagram that Todd Little put together to explore product roles in his organization comes in handy. This diagram, modified from Todd’s original, shows that there are three primary models to apply specific titles to these roles.

The models differ in the number of product people that sit between customers and the product team and what organization those product people report through.

There seems to be general agreement that the ideal model is to have a single product person working to understand customers and building a shared understanding with the product team. This is the Only Child model shown above. The reasoning goes that the best person to build a shared understanding with the product team is the one who is working to understand their customers.

Most startups use the Only Child model where the founder is filling the product management role. As the product gets more complex and the organization grows, you may see someone brought in to be a full time product person so that the founder can concentrate on other things.

As the product continues to grow in complexity, you’ll reach a point where one person, even if acting only as a product person, can not effectively put forth the effort to understand their customers, and build a shared understanding with the product team. This usually coincides with the need to add more product teams to the mix.

Some organizations keep the number of product people to one per product team in which case you have multiple instances of the only child model.

In other cases, organizations split up the product responsibilities so that you have one or more people focusing on understanding the customers and other people who focus on building shared understanding with the product team(s). These are the Identical Twin and Fraternal Twin models. The difference between these two models is the organization in which the product person reports. This difference is important because it can impact how product people interact with each other.

External product titles and roles: Who does what?

Once you know whether you want the same person to fill both product management and person roles, you then need to decide who should fill those roles. Specifically, what titles the people who those roles have and the relationship between the product people when there is more than one.

The different views about roles and titles are usually based on the community where you tend to get most of your information about product development.

If your primary source about product development information is the scrum community you’ll probably suggest that there should only be a single product person, and that person is a product owner. Discussion of a product manager rarely happens, unless it’s to say some variation of “If you have a product manager, you’re not doing scrum.”

If your primary source about product development information is the product management community, you’ll suggest that the single product person is a product manager. If there are multiple product people, the product manager is the one interacting with customers and the product owner is the one who primarily interacts with the product team. The product manager is usually the one making the broader decisions.

I’ve spent considerable time interacting with both communities, and have explored how several different organizations relate titles to roles. In practice it looks like most organizations are closer to what the product management community describes. As a result, I prefer to describe the various product people models in those terms, as is reflected in the diagram above.

Titles and roles in an internal product setting

The previous section explored product people titles and roles in an external setting, especially the product manager/product owner quandary. Now it’s time to look at the internal product setting.

This setting has some interesting twists with the addition of business analysts, a reduced focus on product management, and some interesting modes of operation for product owners.

Product Roles

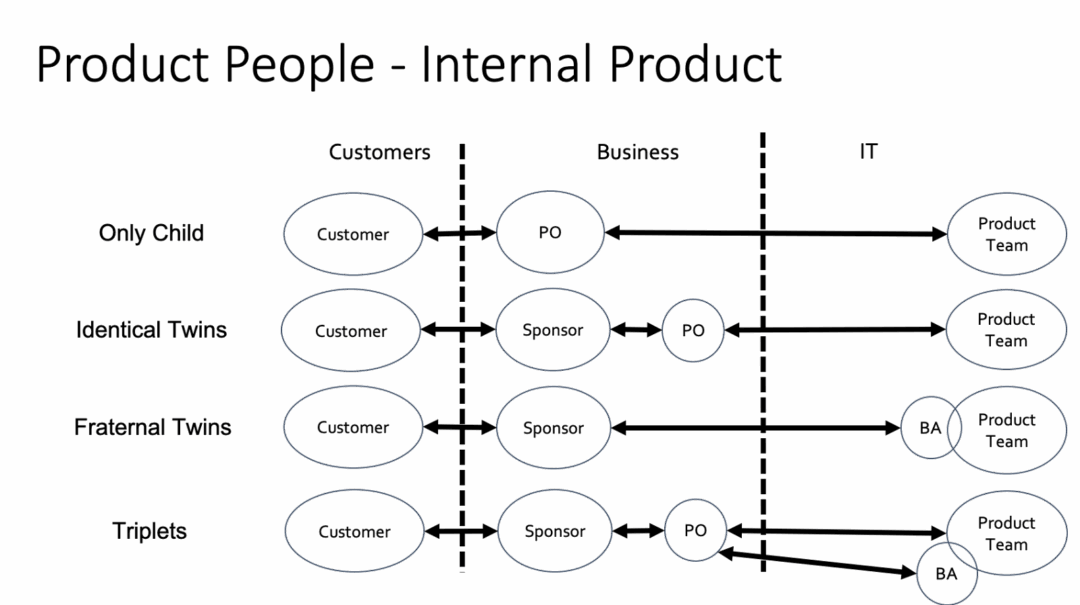

Internal product settings have the same roles as external product settings, with the addition of business analysis.

You fill the product management role when you work to understand customers and are outward focused.

You fill the product ownership role when you build a shared understanding of the problem to solve with your product team and are inward focused.

You fill the business analysis role when you work to build understanding of the data, rules, and processes that your team needs to work with. Understanding the data, rules, and process provides structure around your solution.

You may be thinking, “wait a second, I’ve worked in an internal product setting for a while and don’t really remember a product manager…”

Yep.

In an internal product context, there may not be an explicit product management function. The connection with customers and decision-making activities usually occurs in various business units (or, in more cases than I care to admit, decision-making responsibility does not seem to rest anywhere). In this situation, product management happens in a sponsorship mode.

When you act in a sponsorship mode, you still make decisions about the problem to solve and constraints on a solution (i.e. time and budget). You still make those decisions based on your understanding of the impact to your business and it’s customers.

The difference is that you aren’t responsible for a specific product that is sold to your customers. You aren’t responsible for marketing and selling a product. You are more than likely responsible for a process that enables delivering a product or service for your organization’s customers.

And, being a product person is not your full time job. That point is key when looking at the different models for organizing product people in an internal setting.

Models for organizing product people

When Todd Little originally showed me his diagram of models for how to organize product people, I applied the diagram to both external and internal settings.

Then I started considering organizations through the perspective of the model and spent some time inside an internal product setting. I realized that the characteristics of external products and internal products are different enough to warrant different sets of models for the two settings.

Only Child

Just like the external product setting, it’s still ideal to have a single product person working to understand customers needs, building a shared understanding with the product team, and understanding key data, rules, and processes. This is the Only Child model shown above.

This model works as long as the product person is doing product work full time and has the appropriate authority and responsibility to make the necessary decisions.

Those conditions rarely exist in practice so organizations adopt one of the other models, but rarely on purpose.

Identical Twins

In some cases, an organization identifies someone who is supposed to act as product owner, but they do not have full decision making responsibility about what problems to solve. The organization ends up in an Identical Twins model, although the sponsor may not be explicitly identified.

Fraternal Twins

When the product person has the appropriate decision making responsibility, but is not working on product full time, you’ll often see the product team taking on significant portions of the product ownership and business analysis roles. They effectively act in the Fraternal Twin model.

You may also use the Fraternal Twin model if the product person identified in the business unit does not have the appropriate skills to effectively build an understanding of related rules, data, and processes.

Triplets

Your organization may adopt the Triplets model when the person in the business unit who was identified as the main product person has neither the responsibility to make all the decisions (usually around what funds are available to work on the product) nor time available to work directly with the team.

This model is characterized by someone acting in sponsorship mode who makes key decisions about funding work on a product, and what particular problems to solve. Though to be honest that second decision usually ends up being about what solution to deliver.

A product team will identify someone to do business analysis for one or both of two reasons.

- When the person filling the product ownership role cannot devote their full attention to working with the product team.

- When the product person filling the product ownership role does not have the skills to build the necessary understanding of data, rules, and processes with the product team.

It’s helpful to know what model you want to use, but you also need to consider who is going to fill the roles in whichever model you pick. In fact the two are fairly intertwined.

Titles and Roles: Who does what?

When you’re trying to decide who will be the product people in an internal product setting, start with who can make the key decisions about what problem to solve and how much to spend to solve that problem. Typically this will be a leader in the business unit that has the problem that needs to be solved.

The Sponsor

Unless that leader is going to put aside all of their other responsibilities, don’t call them the product owner, it will only lead to confusion. Instead, ask that leader to act as a sponsor. As a sponsor, they’ll make key decisions about the problem to solve, when that problem should be solved, and how much it’s worth to the organization to solve that problem.

The sponsor should provide air cover for the product team. Providing air cover includes protecting the team from distractions and removing obstacles from the product team’s path.

The sponsor should also identify who is going to fill the product ownership role.

Product Owner

The sponsor should identify someone who has the authority to make informed, timely decisions and can spend the appropriate amount of time working with the product team. Find someone that can do product ownership as a full time gig, not a side hustle. That person is your product owner.

That product person may be from the business unit impacted. These product owners are generally subject matter experts and will have a good understanding of the specifics of the business rules, process, and data that they need to support. That can be very helpful, but they may not have experience building a shared understanding with the product team.

The product owner may want to pick up those skills, or they may not realize that they need them in which case the product team supplements those skills. Often you’ll see a scrum master, or delivery lead filling that gap. That’s especially the case if the person filling the scrum master or delivery lead role has a business analysis background.

You may choose to favor experience building a shared understanding with the product team over subject matter expertise and identify a product owner from the IT organization. This is more than likely a business analyst.

Business Analyst

If a business analyst fills the product ownership role, they need to be able to make key decisions. The sponsor has to be willing to let the business analyst make decisions, and the business analyst needs to be willing to make those decisions.

If the business analyst is willing to make the decisions but the sponsor isn’t willing to give them the authority then the business analyst’s responsibility is to “make sure decisions get made.” If the business analyst does their job right, the product team will not notice a difference. The team won’t experience interruptions due to delays in decision making, they just may not know who made the decision.

You may also have a scenario where there is a product owner and a business analyst (the Triplet model described above). In this case the product owner makes decisions and builds shared understanding about the problem. The business analyst applies their business analysis skills to provide specifics about the relevant business rules, data, and processes in a way most useful for the product team. The more complex the product, the more likely you’ll see this model.

What product model do you use?

I put these models together to remind you that there is not one way to organize your product people. I wanted to stress the impact that context has on how you organize product people. For example, there are a variety of perspectives on the relationship between product managers and product owners. Each organization chooses the model that they feel works best for them.

The main consideration for picking the proper model is whether you’re working in an external product setting or an internal product setting. Then you need to think about and to give you an idea of different approaches and provide some thoughts on which model might work for you.

I want to make sure I’m always testing these models against reality. If you have some insights into the models I’ve shared, leave a note in the comments. I’d love to hear whether you’re working in an external or internal product setting and what model you’re using.