What Is Story Mapping

A story map is a visual representation of a backlog that provides additional context regarding how backlog items are related to each other and when the team is planning to deliver them. This context is typically presented in terms of the personas that will use specific features, and the particular user stories that are associated with the features.

An Example

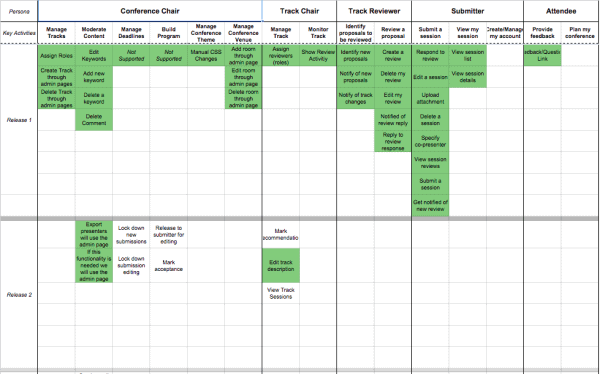

Here is an example story map for the conference submission system.

When to Use Story Mapping

Story maps as originally described by Jeff Patton are a very helpful elicitation technique when trying to understand a solution that has a great deal of user interaction. Creating the story map guides the team as they talk through the business process, identify the key activities (represented as features), and lay them out in a logical sequence.

There are many cases where the solution does not inherently support a single process or a logical step-by-step order is not so clear. In those cases, story maps can still be useful for visualizing the relationships between features and user stories and representing when specific user stories will be delivered for a given feature.

Why Use Story Mapping

The unique visual structure of story maps helps the team determine if they have a complete, viable solution.

Story maps also help teams identify the appropriate contents of a given release. The release goal should be to deliver the minimum acceptable functionality while still providing a viable, valuable output with enough useful functionality for stakeholders to provide feedback about. Story maps help the team identify that minimum feature set.

Finally, story maps provide a useful graphical representation that shows which stories are planned for a given release and relates that in context to the features they support. It also encourages discussions about what aspects of a feature really need to be delivered. In many cases, a feature represents a broad area of functionality, and the user stories identified for that feature represent things that have to be done, things that are nice to have, and other things that could easily be considered bells and whistles. The story map generates conversations where the team determines the things that need to be delivered and skips the items that are nice to have. This delivers on the objectives of the solution without wasting time and effort on functionality that doesn’t add to its effectiveness.

How to Use It

The Story Map as an Elicitation Tool

Gather together key stakeholders and team members. You want to strike a careful balance between having different perspectives in the group and having an unwieldy number of people. A general guideline is to follow the two-pizza rule: a good-size group is one you can feed with two large pizzas.

You’re also going to want a large surface, either a wall or a table, where you can lay out the sticky notes or index cards you use for the map. Some groups have even resorted to using the floor.

Jeff Patton suggests the following steps for using a story map in an elicitation setting. This technique is especially helpful when eliciting information about a process.

- Write out your story one step at a time.As a group, talk through the various things that happen in the process and write each thing down on a sticky note or index card. Each of these items is a user task, which in this context is a short verb phrase that describes something people do to reach a goal.

- Organize your story. If you weren’t already doing so when you identified the tasks, arrange them from left to right in the order they occur. This creates a narrative flow and implies the phrase “and then I . . .” between the tasks. If there are certain tasks that happen at the same time or in lieu of each other, place them vertically in a column.

- Explore alternative stories. Once you have the tasks in a rough narrative flow, play “What About.” Discuss alternative things that could happen at various points during the story. Write these thoughts on additional sticky notes or index cards and place them in the appropriate column.

- Distill your map to make a backbone. Review all the tasks and where they combine into common groups, and use an easily distinguished note (for instance, a different color or shape) as a group title, or activity. The activity should also be written as a verb phrase that distills all the tasks under- neath it. These activities should also form a narrative flow and provide the outline of a high-level story.

- Slice out tasks that help you reach a specific outcome. Identify a specific outcome that you want to accomplish, and then identify the specific tasks that are absolutely essential to arriving at that outcome. Leave all the activities at the top of the story map, but move the tasks that don’t contribute to the particular outcome below the line for that outcome. This step allows you to focus on only the tasks and activities that are essential to accomplishing your desired outcome. Those outcomes can be thought of as a “happy path” through a process or a minimum viable product.

When you are ready to start delivering the solution represented by the map, you can think of each task as a user story. You especially benefit from the fact that the tasks are already written from a user perspective.

The Story Map as a Backlog Visualization Tool

Even if you are working on a solution that does not have a large amount of user interaction or does not clearly support a business process, the story map format can still help you understand the context of your backlog.

- Frame the problem. Establish a shared understanding of what need the solution is intended to satisfy. The techniques described in Chapter 13 can be especially helpful here.

- Map the big picture. Lay out the story map using features as the high- level items across the top of the map. If you have different types of users who can use specific types of features, it may be helpful to organize the features by user. If there are any obvious user stories that can be identified for those features, place them under the appropriate feature at this point.

- Explore. Select the feature(s) you believe you will be delivering first and do a deep dive on them via conversation with the interested stakeholders. Sketch models to aid the conversation (you may find those sketches helpful later on when you start delivering those particular stories). As you have those discussions you may find that you will refine your map.

- Slice out a release strategy. Look at the user stories identified for the features and determine the minimum user stories needed to deliver the desired goal. The idea is to identify the minimum output to deliver the maximum outcome. Organize these user stories into a set of releases by moving them vertically.

- Identify the items to start with. Once you have identified a set of releases, you may find it helpful to identify the user stories you want to start with, as experiments where you are either trying to validate key assumptions or reduce risk. These stories become the topics of your first iteration.

Caveats and Considerations

It’s very likely that you will identify and place more items on your story map than you actually deliver. This is appropriate and expected, as one of the reasons for a story map is to identify user stories that are needed and those that are extraneous in the broader context of what you are trying to accomplish.

If you have used the story map to elicit information about a process, it may be difficult to identify names for the activities, as the grouping may not be as natural as the individual tasks. When trying to name these activities, think about what your users/stakeholders would call them.

Do not try to use story maps in isolation from other techniques. They are ultimately an aid to collaboration and conversation, whether you are using them for elicitation purposes or to visualize the backlog.

Story maps can also be used to familiarize people with the process the solution is supporting. Members of the team can walk new folks through the process using the story map as a visual aid.

Additional Resources

User Story Mapping: Discover the Whole Story, Build the Right Product. By Jeff Patton O’Reilly Media, 2014.

User Story Mapping presentations by Jeff Patton

Story Mapping Agile Alliance Glossary Item

Five Common Story Mapping Mistakes

Jeff Patton shares some of the common mistakes he sees people and teams make when they create and work with story maps:

- Losing the story

- Getting lost in the details

- Worrying too much about flow, branches, and what-abouts

- Mapping the whole product when you’re trying to add a single feature

- Not anchoring releases on an outcome

Want to know more?

If you learn better with video rather than reading, you may want to check out Analysis Techniques for Product Owners Live Lessons, a set of video training sessions that show you how to apply analysis techniques to product ownership. Lesson 5.2 focuses on story mapping.

Analysis Techniques for Product Owners is available on Safari – O’Reilly’s online learning platform. Sign up for a 10-day free trial to view the video lessons.