The success of products and initiatives is highly correlated with well-informed, timely decisions. As a result, decision making is one of three key activities of product ownership.

When you’re the person on the team responsible for product ownership, you make sure that decisions get made. These decisions range from broad decisions about the entire product down to specific day to day decisions on very specific design aspects of your product. You don’t make all of those decisions yourself, but you certainly play a role in making sure that whomever does make the decisions does in in a timely and informed manner.

There’s more to decision making than simply flipping a coin and calling heads and tails. As I reflect on the successful and not so successful decisions I’ve made, I’ve found the following aspects important to consider:

- What Decisions

- Who Decides

- When to Decide

- How to Decide

- Evaluate Your Decisions

This post explores each of these aspects at a broad level. For a more indepth exploration, Kupe Kupersmith and I have started work on a product person’s guide to making effective decisions. Let us know if you’d like to see early drafts and provide feedback.

What Decisions

Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden noted in Sense and Respond “for information workers, thinking and decision making are the work.”

From the product ownership perspective, that work consists of a set of decisions that you make for every product. Generally speaking those decisions include:

- What is the need to satisfy?

2. What are some possible solutions?

3. What should we do next?

4. What are the details of this part?

What Is the Need to Satisfy?

In order to make this decision your team needs to understand your stakeholders, their needs, and which of those needs, if any, are worth satisfying. This evaluation has two aspects: stating the need, and ensuring that everyone involved has a shared understanding of the desired outcome.

Also extremely helpful at this point is the clarification of goals and objectives, which helps your team answer the question “Do we know what success looks like and how to measure it?”

While making this decision your team needs to determine “Is this need worth satisfying?” If so, move forward. If not, stop right here.

What Are Some Possible Solutions?

Don’t assume that there is only one solution for a given need. Identify multiple possible solutions, note the differences among those options and understand ways of identifying and assessing them.

It’s at this point where you’ll examine whether to build versus buy a solution, and depending on that choice, choose from different designs or different packages.

Ask, “Is this need worth satisfying with this solution?” about every potential solution, pushing aside solutions that do not make sense.

To guide this decision you’ll find it helpful to have clearly defined conditions of satisfaction. What must be true in order for a particular solution to satisfy the need in a way that you want.

What Should We Do Next?

This is the decision you make to determine what which solution, or part of a solution, to deliver to stakeholders next.

Revisit the backlog on a regular basis to incorporate revised understanding of the need and how you believe the solution is working to solve it.

Evaluate how well the identified solution satisfies the project’s objectives.

And then based on all that, make a continue, change, kill decision about the product.

What Are the Details of This Part

Once your select the next part of the solution you are going to deliver, build a detailed shared understanding of that part of the solution for purposes of delivery.

Decisions you and your team make at this point include “Do we know enough to deliver this part?”, “Should we deploy?”, and all the specific design and implementation decisions that are a part of product development.

This iterative approach to decision making allows your team to gradually dive into detail about your solution, taking advantage of the learning you receive from delivering earlier output. This iterative approach also provides your team with regular opportunities to decide whether to continue, change or kill your product.

Who Decides

The person who is responsible for product ownership should make sure decisions get made. That implies that if you are the one responsible for product ownership, you are not going to make all of the decisions yourself.

The person who makes a specific decision should be as informed as possible and in a position to make the decisions stick. That’s usually the person closest to the work. So if you follow this line of thinking, spread decision making out into the organization.

That said, decision making is most effective when a single person rather than a committee makes a decision.

So how do you address this seeming paradox? The key is to identify the one person who makes each specific kind of decision, and realize that different people will make different decisions.

You will own some of those decisions, members of your organization’s leadership and members of your team will own others. It’s helpful to discuss decision making responsibility when your team starts work on a product and revisit those decision making responsibilities when conditions or the team changes.

So even though you don’t own all the decisions, you should own making sure your team has determined who does make what decisions.

When to Decide

Most people dislike uncertainty. They would rather take the risk of making a wrong decision now than live with the uncertainty for as long as necessary to improve their chances of making the right decision later. Instead of making a decision right away with limited information, determine when that decision needs to be made, in terms of either time or the conditions that need to be met. In the intervening time, collect and investigate information that improves your chances of making the right decision.

How do you determine the appropriate time to decide?

Most decisions involve selecting from a set of options, each of which is available to you for only a certain amount of time. You have until right before the first option disappears to make your decision, gathering information in the meantime. Even then you may not need to make a final decision; you really have to decide only if you want to go with the expiring option, or if you would rather use a different option.

How to Decide

Decision making can be a fairly vague concept, so here’s some structure to help explain how to approach the act of making a decision:

- Select a decision mechanism.

- Determine what information you need.

- Build support with peers/stakeholders.

- Communicate the decision.

- Enact the decision.

Select a Decision Mechanism

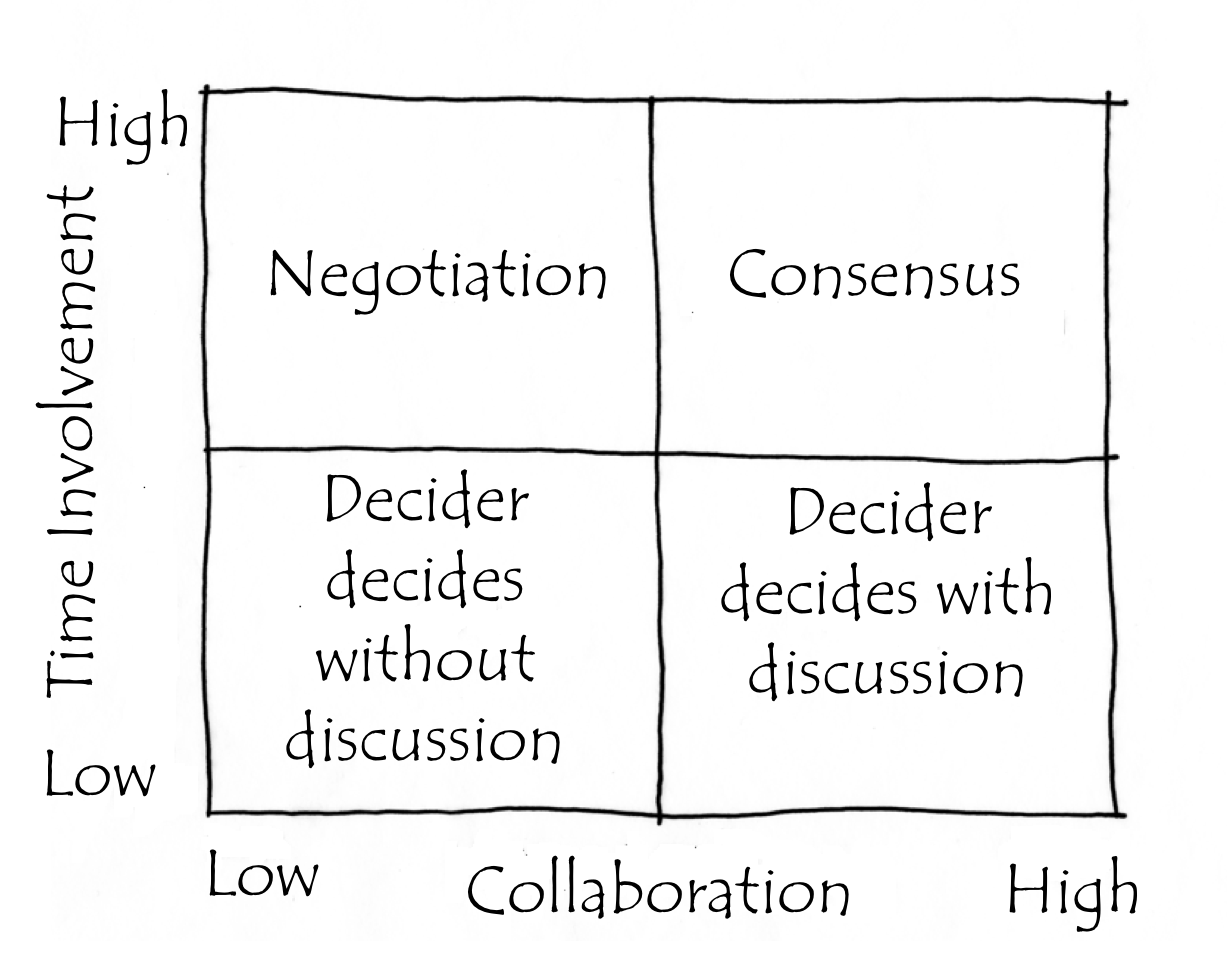

Knowing who is going to make a decision impacts the mechanism used to make the decision.

Constraints such as how much time you have available and how much collaboration you feel is necessary can also impact your approach.

You can use the combination of those two characteristics to guide your selection of an approach

Determine what information you need

In order to make an informed decision, determine the relevant information you need to make an informed decision. The information you need varies on the decision you’re making, and it can be helpful to use mental models to structure the information for any given decision.

For example, In Stand Back and Deliver, Pollyanna, Niel, Todd, and I discussed the business value model which we’ve found to be a very helpful way for identifying and organizing the information necessary to make many of the significant product related decisions I mentioned above.

A key thing to consider when you pull information together to help you make a decision is to do so in a way that helps you to counteract cognitive biases—patterns of deviation in judgment that occur in particular situations.

Build Support with Peers/Stakeholders

Your decision making method impacts how much time you need to spend building support with your peers and other stakeholders once you make the decision.

If you decided by consensus, you already have the support of everyone involved in making the decision. Deciding with the input of others will help you build support, especially if you listened to and considered input from the key people whose support you need.

If you are the sole decision maker, you have a bit more work on your hands. If you make decisions in a dictatorial manner, you may have a harder time building support and may never fully win the support of everyone involved.

Communicate the Decision

Once you make a decision, you should make sure those whom you expected to be involved in enacting the decision, and those impacted by it, know about it. The way in which you communicate the decision may be a key aspect of how you build support, especially for those stakeholders who wouldn’t normally expect to be involved in making the decision.

Enact the Decision

When making a decision, it’s best to think about how it will be enacted at the same time. The execution of a decision can play a huge part in whether it produces the results envisioned by the person or people making the decision.

Evaluate your decision

Once you’ve made and enacted a decision you should reflect back and see how you did. Determine if the decision was right by comparing the actual outcomes with the objective you were targeting.

Evaluate the process you used to make sure that you had the information that you need, and that you made the decision at the right time. Not too early to lose out on key information and not too late such that desirable options expired.

Conclusion

What lessons have you learned about decision making during your career? What tips and techniques or questions do you have about decision making? Leave your thoughts in the comments.