It’s not quite a 2×2, but it’s still very helpful.

What It Is

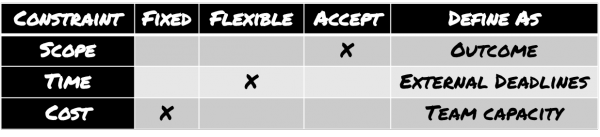

The constraints matrix is a quick way to show the relative importance of a set of constraints facing a project team. Each row represents a general constraint faced by most teams. The most common set to use are: Cost, Time, and Scope (ie the Iron Triangle).

The columns represent the amount of change that can be accepted for each constraint when trying to deal with an overall project change.

- Fixed: no changes are desired in the constraint unless all other options have been exhausted.

- Flexible: a change can occur in this constraint only after the options that made changes in the constraints marked accept are exhausted.

- Accept: the constraint is the first place to adjust to account for a change in the project.

Some additional rules for using the Constraints Matrix:

- Each constraint can be in only one column Fixed, Flexible, or Accept.

- There can be only one Fixed constraint

- There can be only one Flexible constraint.

When To Use It

Use the Constraints Matrix to help guide a conversation with the project sponsor to determine the relative importance of key project constraints.

Use it to have the initial conversation with the project sponsor at the beginning of a project to set an initial understanding of the relative importance of the constraints.

Provide the matrix to the entire team to help them make decisions as they proceed through the project and are trying to determine how to deal with changes in the project environment.

Revisit it frequently with the project sponsor to confirm the current relative importance of project constraints.

Why Use It

It helps guide the project sponsor to decide which constraint is actually the most important, and helps prevent project teams from thinking they have to hold more than one constraint absolutely still when changes occur. It also helps provide the team with guidance on the relative importance of the project constraints from the project sponsor’s perspective.

How to Use It

- Explain the matrix to your project sponsor including what the columns mean and the rules surrounding it’s use. Explain that you are using this matrix to help describe the relative importance of project constraints.

- Determine if the set of project constraints is sufficient. If the list is not sufficient, make changes, but do not add too many constraints because all but two of them will be marked as Accept and there fore will not provide valuable information.

- Ask the project sponsor what one constraint is fixed. Resist your project sponsor’s attempts to call more than one constraint fixed.

- Ask the project sponsor what one constraint is flexible.

- Mark the remaining constraints as accept.

- Ask the project sponsor to review the completed matrix and confirm that they agree with this layout. If they would like to make changes, go ahead and do that as long as only one constraint is fixed, and one constraint is flexible.

- Share the finished matrix with the project team and explain how to use it when dealing with project issues.

- When discussing issues with the project sponsor, and they try to hold more than one constraint constant, remind them of the matrix and ask them to revise their decisions accordingly.

Caveats and Considerations

Define time constraints in terms of externally imposed deadlines. In other words time is a real constraint only when there is a compelling business reason for your the project to deliver something at a specific point.

In IT projects or software development work, define cost constraints in terms of the the capacity of the team needed to do the work. This will give you an additional mechanism to determine prioritization and accurately represents how cost is accounted for in most IT projects (availability of a certain team or teams for a certain time period.)

Define your scope in terms of outcome rather than output (list of things to deliver). This provides your team with the flexibility to adjust their plans as they start working on the project, learn more about the problem, and figure out the best way to solve it.

Resource(s)

Highsmith, Jim. Agile Project Management: Creating Innovative Products (2nd Edition), Boston: Addison Wesley, 2010. P.108-109

Note May 20, 2018:

In earlier versions of this post, I included quality as a constraint. However after repeated comments from my friend Joe McCloud that quality shouldn’t be considered a constraint and realizing that Jim Highsmith’s original version didn’t include quality, I revised the matrix to remove it.

To be honest, I’m not sure how quality snuck it’s way on to the matrix. I think I may have put it on there to force a discussion around the reality that teams often end up sacrificing quality in order to fit into the other three constraints. I figured by having it explicitly as a choice more teams might actively discuss whether they want to consider it an option.

Joe’s right, it shouldn’t be considered an option, and it shouldn’t be negotiable. I’ve found a better way to address tight constraints is to always strive for high quality (through good engineering practices) and fit within the constraints through how you define and agree to Scope, Time, and Cost.